1. The Baliol Family-Scottish Nobles

There are several places named Bailleul in France: 1) in Flanders, near the Belgian border (14 miles NW of Lille); 2) Bailleul sur Berthoult (north of Arras); and 3) Bailleul- Orne (between Caen and Alençon). The first location is the recorded point of origin of the family which was to play such an important role in English and Scottish history (1). The founder of the family in England was a Norman baron, Guy, or Guido de Bailleul who held the fiefs of Bailleul, Dampierre, Harcourt, and Vinoy in Normandy. At this time, (about 1066) William the Conqueror was preparing for a conquest of England, and had promised a share of the land gained to any of the Norman barons who would follow him. Guy de Bailleul was one of these, and must have remained in England after the fighting ceased. Around 1093, he was granted the Barony of Biwell in Northumberland (which included the forests of Teesdale and Marwood, and the lordships of Middleton in Teesdale and Gainford, part of the wapentake of Sadberge) by William Rufus, notoriously cruel "Red King", the son of William the Conqueror. This area, which later became the vast parish of Gainford, had been ecclesiastical land before the Conquest, although leased or mortgaged to laymen. In the Boldon Book of 1133, the Baliol fees were not included in the Bishopric. This was the prelude to a long dispute over whether the lands were held of the Bishops of Durham and could be taxed by them (2).

Another family member, Renard de Bailleul, may have been mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086. This Rainald de Baliol (also Renaud, or Renard), was Sheriff of Shropshire under Earl Roger (Roger de Montgomery II), and had accompanied the Conqueror across the channel in 1066. Renard was married to Amiera, Earl Roger's niece. He may be one and the same as Pierre, Knight of Balliol and Fecamp who contributed one ship and twenty men-at-arms at Hastings, or he may be the brother or son of Pierre. Renard's descendents also included several Bishops of Lincoln.

In the late 11th or early 12th century, Renard's son, Bernard de Bailleul (Baliol), began construction of a castle near Durham, overlooking the River Tees. As was common in those days, Barnard Castle acquired the name of its builder. Bernard played a prominent part in history: he fought for King Stephen during the civil war. He was a military commander of some reputation and participated in the victory over the Scots in 1138 at a battle near Northallerton, which came to be known as the Battle of the Standard. Like King Stephen himself, Bernard was later taken prisoner at the battle of Lincoln, on February 2, 1141. The exact date of his death is unknown.

A son, Bernard II, probably was responsible for much building of the family castle in Teesdale. He took a prominent part in local affairs, first being noted in the records around 1167. Bernard II was a munificent benefactor to the church, bestowing lands upon the abbey of St. Mary at York, and upon the monks at Riebault. Bernard II took up arms and, joining Robert de Stuteville, proceeded to the relief of Alnwick Castle in 1174 (3). In the course of this forced march to Alnwick, a dense fog was encountered and a halt was recommended. Baliol is reported to have replied:

"Let those stay that will, I am resolved to go forward, although none follow me, rather than dishonor myself by tarrying here."

In consequence, they all advanced, and the returning light enabled them to decry the battlements of Alnwick Castle. William, the Scottish king, was then in the fields with a slender train of 60 horsemen. At the head of these, however, he instantly charged the newcomers, whose force was much larger. Being overpowered and unhorsed, William was made prisoner by Baliol and sent to the castle of Richmond and afterwards to Falaise in Normandy.

Bernard's daughter, Annabel (1153 - 31 MAR 1204), became a concubine to Henry II Plantagenet. Bernard's son, Eustace, succeeded him in 1215, the same year that King John made peace with his barons at Runymeade. He gave ú100 for license to marry the widow of Robert Fitzpiers. Eustace had three sons: Hugh, Henry, and Eustace II.

Henry married Lora (also recorded as Lauretta) who was one of the co-heiresses of Christian, wife of William de Mandeville, Earl of Essex; and heirs of Peter, lord of the barony of Valoines (Valsques), and lord of Panmure. In 1234, Henry inherited part of the rich English fiefs of the Valoines family. He died in 1245-46, and his widow retained livery of all the lands in Essex, Hertford, and Norfolk which Henry had held of her inheritance. They had two sons: Alexander (d. 1271-72) and Guy Baliol.

Eustace the younger married Hawise, daughter and heiress of Ralph de Boyville de Levyngton, a baron of Northumberland. In 1260-61, the records show Eustace as being sheriff of Cumberland and governor of Carlisle Castle. Nine years later he assumed the cross and accompanied Prince Edward to the Holy Land.

Hugh de Baliol succeeded Eustace (the elder) as head of the family. He was certified by the Crown to hold the barony of Biwell (paying five knights' fees). He also was required to find 30 soldiers for the guard of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, as his ancestors had done since the time of William Rufus. Also, as a gift from Henry II, Hugh was made lord of Hiche in Essex. Later, from King John, he obtained the lands of Richard Unfronville and of Robert de Meisnell in County York -- this for his support of the king in the baronial war. In 1216, de Baliol joined with Philip de Hulcotes in defense of the northern border with Scotland. When the Scottish king subjugated the whole of Northumberland for Lewis of France, de Baliol and de Hulcotes firmly held all the fortresses on the line of the Tees. Barnard Castle was particularly notable in this defense (3). Hugh received King John at Barnard Castle at this time, and for a short while was besieged there by Alexander II of Scotland who wished to "espie whether it was assailable at any side." The castle at that time was apparently too strong to afford an easy conquest (2).

Hugh de Baliol was also described by Dugdale as having "benefitted himself not a little in the troublesome times of King John and, even at the great entrance of Henry III, could not forbear his wonted course of plundering."(2) Hugh was married to Cecily de la Fontaine. Some time around 1228, he was succeeded by his son John who, having been born at Barnard castle about 1216, would have been a meer adolescent at the time.

John became one of the regents of Scotland during the minority of Alexander III. In 1244, when ways and means were required to discharge the debt incurred by the war in Gascony, John de Baliol was one of the committee of 12 chosen to report to Parliament on the subject. The next year, Baliol is reported as having paid ú30 for thirty knights' fees which he held towards the levy in aid for marrying the king's daughter. Afterwards he served as sheriff of Cumberland and governor of Carlisle Castle for six years. Subsequently he had a military summons to attend the king at Chester to oppose the Welsh. He was also sheriff of Nottingham and Derby Counties for three years.

During the time that John Baliol was head of the family relations with the bishops of Durham continued to worsen. This may have reflected the rift between the English bishops and the Crown. Around 1255, the Bishop of Durham excommunicated and, in due course, imprisoned some of Baliol's men. In retaliation, Eustace (John's uncle?) and Jocelyn Baliol waylaid the bishop and threw 4 of his servants into the dungeon. Henry III intervened and brought about an exchange of prisoners.

In the baronial revolt against the king led by Simon de Montfort, Baliol remained loyal to the throne. Along with the king he fell into the hands of the Earl of Leicester at the battle of Lewes in 1264. However, he appears to have effected his escape and to have joined the other loyal barons in raising fresh troops to rescue the monarch.

John Baliol, married Devorguilla, the younger daughter of Alan, Lord of Galloway, a great baron of Scotland. Galloway's wife, Margaret, was sister of John le Scot and one of the heirs of King David. It was from this alliance that the Baliol claim to the throne of Scotland arose. Also, through the marriage to Devorguilla, Baliol acquired the Scottish barony of Galloway. Devorguilla, came to the union with Baliol an equal partner, and her family arms were joined with his.

About 1260, with guidance from the Bishop of Durham, John decided to carry out a substantial act of charity. He did it by renting a house in the suburbs of Oxford, and maintaining in it some poor studnets. The foundation date of the College which grew from this is traditionally reckoned as 1263. At the very least, the little society which John Baliol founded was in existence by June 1266, when its dependence on him is mentioned in a royal writ. After his death in 1268/69, his widow, Devorguilla, put his arrangements on a permanent basis, and she is honored as co-founder with him. She provided a capital endowment, formulated Statutes (1282), and gave the College its first seal, which it still has. Devorguilla and John's union is commemorated in the arms of Baliol College, Oxford.

Their's must have been a true love; when John Baliol died, Devorguilla had his embalmed heart placed in an ivory shrine. This shrine was placed before her at meals, and she would give it's share of every dish to the poor. Later she founded "Sweetheart" Abbey (along with the college). She died in Buittle Castle on 28 January, 1289/90, but was buried in the Abbey with the casket containing John's heart in her arms.

Sweetheart Abbey today

Sweetheart Abbey today

John had three sons, and in 1268 his property came to his eldest son, Hugh Baliol. Hugh died without issue in 1271 and was succeeded by his brother, Alexander. Alexander married Eleanor de Genoure and inherited a barony of more than 25 extensive lordships. Like his older brother, he died without issue in 1278-79 and was succeeded by John Baliol (the younger). John later went on to become king of Scotland (more on that below).

Another branch of the Baliol family which is mentioned in history was descended from Joscelin, son of Guy de Baliol and brother (cousin?) of Bernard. Joscelin's son Ingram (or Ingleram) married Ada, the daughter and heiress of William de Berkeley, lord of Reidcastle in Forfarshire, and chamberlain of Scotland, and by her he had a son Henry, who became chamberlain about 1223.

It is probable that Henry's son was Alexander de Baliol, lord of Cavers in Teviotdale, first mentioned in 1287 as chamberlain of Scotland. He shared in the negotiations between the Scottish nobles and Edward I of England, which resulted in the treaty of Salisbury in 1289 and the treaty of Brigham in 1290. He probably lost his office as chamberlain in about 1296, and may have shared the imprisonment of his kinsman, John Baliol, the king. He then fought in Scotland for Edward, and was summoned to several English parliaments. Alexander's wife was Isabell de Chillam from whom he inherited for life the Castle and manor of Chillam (County Kent). They had sons, Alexander and William, the former who succeeded to the Lordship of Cavers. Alexander died about 1309, and his grandson, Thomas, is the last of the Baliols mentioned in the Scottish records.

2. John Baliol - King of Scotland

A. How he acquired the throne

Alexander III was consecrated as the ruling monarch of Scotland with much pomp and ceremony in 1249. It was said his line could be traced unbroken back to King Fergus, around 500 A.D. Fergus' father had come from Ireland, and Scottish tales claimed that these Irish were descended from the Greeks (by migration through Spain). Alexander's first wife, Margaret, sister of Edward I of England, died in February 1275. In October 1285, Alexander married Joleta (Yolande), daughter of the Comte de Dreux. Of Alexander's children, the younger son, David, died in 1281 when he was eight years old. The elder son, Alexander, died in 1284 at the age of twenty. The king's daughter, Margaret, married Eric II of Norway, and their daughter became know as Margaret, "the Maid of Norway". In February 1284, a week after the death of his eldest son, Alexander III called an assembly of the magnates of the realm together at Scone. The lords acknowledged the "Maid" as heir to the kingdom of Scotland should the king have no other issue.

On the night of March 12, 1286, Alexander was riding from Edinburgh to Kinghorn to join his new wife when he got separated from his guides. In a heavy mist his horse stumbled on a hill of loose basalt trap; Alexander was thrown, and his neck broken.

Six guardians were appointed to administer the realm in the name of Margaret, who was then about three years old. Robert Bruce (the elder) did not accept the authority of the guardianship and, with his son, the Earl of Carrick, made some show of force in a claim to the throne. In September, 1286, Bruce's adherents entered into a bond of mutual defense and assistance at Turnberry, in support of the man "who in accordance with hereditary rights and ancient usages ought to occupy the throne."

In May of 1289, Eric II of Norway sent ambassadors to Edward I to discuss the position of the Maid Margaret as queen of Scotland. The Scottish guardians were also invited to join the discussions which concluded with the treaty of Salisbury. Under this treaty, the Norwegians promised to send Margaret to England before 1 November 1290, "free and quit of all contract of marriage." Edward in turn promised that, if Margaret came to England, and if Scotland remained peaceful, he would send her north also "free and quit of all contract of marriage." The Scottish representatives promised to establish quietness in the land before Margaret came there; and further promised not to contract her in marriage without the "ordinance, will, and counsel of Edward", and save with the assent of the King of Norway, her father.

Unknown to the Scots, Edward had already sent messengers to Pope Nicholas IV applying for the dispensation for the marriage of Margaret to his son, Edward (later Edward II), since they were within the forbidden degrees of the canon law (cousins once removed). The dispensation was granted ten days after the conclusion of the treaty, and the Scots, when they heard of it, agreed wholeheartedly to the proposed marriage. A letter sent from Bingham in March 1290 from the four surviving guardians, eight bishops, twelve earls, twenty-three abbots, eleven priors, and forty-eight barons, spoke of the joyous news of the dispensation and cordially agreed to the marriage. Another letter urged Eric to send his daughter to England.

In July of 1291, a new treaty, the Treaty of Bingham, was signed between Scotland and England. This "marriage" treaty set forth that the "rights, laws, liberties, and customs of Scotland were for all time to be "wholly and inviolably preserved." The Kingdom of Scotland was to remain "separate and divided from the kingdom of England", and to be "free in itself and without subjection." Should Edward or Margaret fail to have heirs, Scotland was to return to the nearest heirs, and the King of England would neither gain nor lose thereby. Other clauses preserved the character of the Scottish parliament, and the independence of the Scottish courts and elections (5). However, Edward managed to insert a specific sentence in these clauses "saving always the right of our lord king [of England] and of any other whomsoever, that has pertained to him, or to any other, on the marches,, or elsewhere, before the time of the present argument, or which in any just way ought to pertain to him in the future."

In May of 1290, a great ship was sent from Yarmouth to bring the Maid to England. The ship was stocked with such childish delights as sugar loaves, gingerbread, raisins, and figs. However, Eric, would trust his daughter only to Norwegian ships. In September, 1290, Margaret embarked from Norway, but never reached her destination. Somewhere in the Orkney Islands she perished "between the hands of the Bishop Narve (of Bergen) and in the presence of the best men who accompanied her from Norway." Her corpse was returned to Bergen and interred beside her mother in the choir of Christ's kirk.

The death of the Maid of Norway upset all of Edward's plans for a peaceful union of Scotland and England. A letter from William Fraser, Bishop of St. Andrews, addressed to Edward I on October 7th, reported that, upon a "sorrowful rumour" of the death of the queen reaching the people, the kingdom of Scotland had become disturbed. Robert Bruce had come with a great following to Perth; the Earl of Mar and Atholl were collecting their forces; parties were beginning to form, and there was fear of general war which could be averted only by Edward's good services. The letter continued: "If Sir John Baliol should come to your presence we advise you to take care so to treat with him that in any event your honour and your advantage may be preserved"; and, if indeed the queen be dead, then let Edward come to the border to console the people, to save the shedding of blood, and to set up "for king the man who ought to have the succession, provided he will follow your counsel."

There were in all, thirteen claimants for the throne, each believing that he was the rightful heir.

1. John Baliol

2. Robert Bruce

3. John Hastings

4. John Comyn or Cummin, Lord of Badenoch

5. Florence, Earl of Holland

6. Patrick Dunbar, Earl of March

7. William de Vescey

8. Robert de Pynkeni

9. Nicholas de Soules

10. Patrick Galythly

11. Roger de Mandeville

12. Robert de Ross

13. Eric II, King of Norway (through Margaret)

During the reign of Alexander II, when he was still childless, the magnates of the realm chose Robert Bruce to be his successor. This decision was based on Bruce being the son of the second daughter of the king's uncle, David, the Earl of Huntingdon. Devorguilla was the daughter of David's eldest daughter. John Baliol claimed his right as the grandson of the oldest daughter, Margaret; while Robert Bruce, Earl of Annandale, said he had superior right to the succession because he was one generation older than Baliol, and therefore nearer the common ancestor; John Hastings was descended from the youngest daughter, and holding the title of Lord of Abergavenny. The lines of descent were less direct for the other ten claimants.

At this time, most countries were adopting the hereditary principle in regard to the succession of their kings. It was a relatively new practice however, and many problems arose, one of these being that of Baliol, Bruce, and Hastings as descendants of the same heir. No one in Scotland could possibly name one of these three as king without having a civil war on his hands. In those days, the custom in this type of dispute was to call on a foreign king who could supposedly view the situation impartially and pick the new ruler. Edward I, the King of England, stood in a curious relationship to Scotland. He was the brother-in-law of the dead Alexander; he was feudal superior of the Scottish monarch for great estates in England; the most powerful Norman nobles in Scotland owed him fealty for English lands; Eric or Norway was deeply in his debt. It was natural that the Scottish leaders should, with the approval of the people turn to Edward for help; the two neighbors had been on friendly terms for a century.

Edward seized upon the chance of settling the dispute, thinking that he could easily turn the tables so that he gained control of Scotland. On April 16, 1291, a summons went out to the barons of the northern counties to attend Edward at Norham. There, on May 10th, Edward established his right to chose the successor to the throne. The Communitas (the whole body of prelates, lords, and important men; the "good men" of the realm) objected to giving him this authority. Such a claim, they declared was new to them; they had no knowledge of any previous claim by Edward, or by any of his predecessors, for recognition as "supreme lord of the realm". Moreover, how could they admit Edward's claim when they had no king, to whom alone such a claim should be made and who alone could answer it? In the end, the objectors were not heeded.

All those making a claim were made to swear allegiance to Edward I and accept him as Lord Superior of Scotland. Scottish nobles, debating the issue, dared not refuse; for Edward, with the might of the English army, would take their country by force, making matters much worse. Also, those Anglo-Norman nobles with extensive estates south of the border stood to lose much by challenging the king. Finally they gave Edward his answer; how, they asked, could they make such a momentous decision without the counsel of a king? If he would name their king, they would consider the matter. Ten claimants made the oath without hesitation as they were all of Norman descent and, even though they had Scottish estates, they were disliked by the Scots. Baliol was the last to swear allegiance because he was absent from the first few meetings.

There were thirteen meetings from May to August in 1291 where the claimants pleaded their claim before Edward. His first decision lay between either Baliol or Bruce, and Hastings. Hastings wished the kingdom to be divided in three equal parts, for the three men; while Baliol and Bruce maintained that the country was indivisible. The Scots obviously wanted to keep the country together, so Hastings was disqualified. On August 3rd, Edward asked both Baliol and Bruce to choose forty arbiters while he chose twenty-four, to decide the case. There was then an adjournment until June, 1292. Upon reconvening, the 104 arbiters wouldn't make a firm decision on the claimants. There was another recess until October 10, 1292, and at this time Edward got the arbiters to agree that as Lord Superior of Scotland had the right to grant the kingship of Scotland as he would an earldom or barony. He chose Baliol on November 17, 1292. On November 30, Baliol was inaugurated on the Stone of Scone, the last Scottish king to be so invested.

B. Problems of his reign - how he lost the title

Without doubt it was an honor for John Baliol to acquire the Scottish throne, but it certainly brought trouble upon him and the country. After his coronation, the two countries were peaceful for a time, and all might have gone well, had not Edward wished to press his authority still further.

Edward insisted that all appeals from the courts of the King of Scotland should pass through the English courts. Edward kept calling Baliol to London to answer for petty cases. A Gascon wine merchant sued in England for payment of a wine-bill for 2,197 pounds which he said was owing to him by Alexander III, and Baliol was summoned to Westminster to plead. Scottish castles were tamely handed over to English garrisons as guarantees of good behavior. Ships laden with corn for Scotland, where there was a shortage of provisions, were seized by Edward's bailiffs. As the last straw, Edward demanded that Baliol send forces to help the English fight the French. Instead, the "Toom Tabard" (empty jacket), as his contemptuous subjects styled Baliol, expelled Englishmen from Scotland, forfeited their estates (Bruce being one of the sufferers) and concluded a treaty with France. [some histories imply that Baliol may have been confined by his nobles and had no say either way in these actions.]

The Scots themselves would not have been able to stand up to Edward and the mighty English army, but with France backing them, they dared to try. When Edward heard of the alliance with France, he was enraged, and made effective reply. As he crossed the Scottish border, Baliol sent to him renouncing his homage. Edward is said to have remarked, "Has the felon fool done such folly? If he will not come to us, we will go to him."

He besieged the great merchant town of Berwick, and captured it after heroic resistance. There followed thirty-six hours of the most hideous butchery and destruction. The castles of Dunbar, Roxburgh, Edinburgh, and Stirling were easily taken; Baliol renounced his crown. He also renounced his alliance with Philip IV and about the same time appeared before Edward at Montrose and delivered to him a white rod, the feudal token of resignation. On July 10, 1296, Baliol forfeited all of his lands to Edward I. Baliol was carried off and never again seen in Scotland. With John Baliol gone from the scene, Anthony Bek, the Bishop of Durham, made good on the claims of his see and, in 1296 seized Barnard Castle.

Baliol was imprisoned in the Tower of London between 1297 and 1299. Indeed, he was one of the earliest residents of the "Salt Tower", also known as the "Baliol Tower, located at the southeast corner of the Tower complex's inner ward (4). John Baliol was delivered from prison in July 1299 by a representative of Pope Boniface VIII. He was then placed in the keeping of the papal delegate who had been sent by Boniface to negotiate peace between England and France. Baliol agreed to live wheresoever the pope directed him. He left England for his French estates and did not return, though he apparently continued to be regarded by many Scotsmen, including Wallace, as the sovereign of Scotland. He died at Castle Galliard in Normandy, in April, 1313 (also reported as 1314 and 1315); he is supposedly buried in the Church of St. Waast at Bailleul-sur-Eaune.

Edward set up no more vassal kings. He declared himself to be the immediate ruler of Scotland, Baliol having forfeited the crown by treason. The Scottish nobles did homage to him. On his return to England, he left behind him the Earl of Surrey and Sir Hugh Cressingham as guardians of the kingdom, and he carried off from Scone the stone of destiny on which the Scottish kings had been crowned, and concerning which there had been an old prophecy to the effect that wherever that stone was Scottish kings should rule. The stone was placed under the coronation-chair of the English kings in Westminster Abbey, and was only returned to Scotland in 1996, seven hundred years after it was first taken.

Edward's actions, however, stiffened Scottish resolve as nothing else could have done. The abdication of John Baliol marks the beginning of the War of Independence for Scotland, which has been written of extensively elsewhere -- and was the subject of a major movie, Braveheart. It was this war in which the deeds of Willliam Wallace were immortalized. It was also the war in which Robert the Bruce finally came to power as king, following his murder of John Comyn. However, this was not the last heard of the Baliol family in the affairs of Scotland.

C. The Return to the Throne

John Baliol's eldest son, by his marriage with Isabel, daughter of John de Warenne, Earl of Surrey, was Edward Baliol, who shared his father's captivity in 1296. On the death of his father, Edward succeeded to his estates in France where he resided in a private manner for several years. In 1324 he was invited to England by Edward II to be brought forward as a rival to Robert the Bruce, and in 1327, at the request of Edward III, he again visited England with the same object.

His real opportunity came after the death of King Robert the Bruce in 1329. Some of the Anglo-Norman barons possessed estates in Scotland which were forfeited during the war with England. By the treaty of Northampton in 1328, whereby the independence of Scotland was secured, the English barons' Scottish estates were restored. But treaty and fact are two different things. Two barons, Thomas Lord Wake and Henry de Beaumont, having in vain endeavored to procure possession of their Scottish lands, joined Baliol when (after the death of the Bruce) he resolved to attempt the recovery of what he considered his birthright.

In Caxton's Chronicle, it is stated that in 1331, having taken the part of an English servant of his who had killed a Frenchman, Baliol was himself imprisoned in France, and only released on the intercession of Lord Beaumont, who advised him to come over to England and set up his claim to the Scottish crown. King Edward did not openly support the enterprise. With three hundred men-at-arms and a few foot soldiers, Baliol and his adherents sailed from Ravenspur on the Humber -- then a port of some importance though now overwhelmed by the sea -- and landed at Kinghorn. On August 6, 1332, they defeated the earl of Fife who endeavored to oppose them. The army of Baliol increased to three thousand men and marched to Forteviot, near Perth, where they encamped beside the River Earn. Opposite, on the Dupplin Moor was camped Donald, the earl of Mar, and regent of the kingdom, with upwards of 30,000 men. At midnight, Baliol's force forded the Earn and attacked the sleeping Scots. Several thousand were slain, including the earls of Mar and Moray. Baliol then hastened to Perth where he was unsuccessfully besieged by the earl of March, who's force he dispersed. On September 24, 1332, Edward Baliol was crowned king at Scone. On February 10, 1333, he held a parliament at Edinburgh, consisting of what are known as the disinherited barons, with seven bishops, including both William of Dunkeld and, it is said, Maurice of Dunblane, the abbot of Inchaffray. His good fortune now forsook him. On December 16 of that year, he was surprised in his encampment at Annan by the young earl of Moray and others, and his army overpowered. Edward's brother, Henry, and many of his chief adherents were slain, and he himself, nearly naked and almost alone, escaped to England.

The year before, on November 23, 1332, Baliol had acknowledged Edward as superior lord of Scotland. Now Edward III came to his rescue at the head of an army which crossed the border and defeated the Scots at Halidon Hill on July 19, 1333. Baliol was once again returned to the throne for a brief space. He renewed his homage to Edward III and ceded to him the town and county of Berwick, with the counties of Roxburgh, Selkirk, Peebles, Dumfries, and the Lothians in return for the aid he had been rendered. However, Edward Baliol could not hold his throne against the Scottish nobility. In 1334 he was again compelled to fly to England. In July, 1335, he was restored by the arms of the English monarch. In 1338, while holding court at his nominal capital at Perth, he was attacked by Robert Stewart and again made a fugitive. Several attempts to reclaim the throne in following years amounted to little, and he finally gave up Scotland completely in 1356 at Roxburgh, selling to Edward III his claim to the sovereignty and his family estates in return for 5,000 merks, and a yearly pension of 2,000 pounds sterling. Edward de Baliol retired into obscurity and died childless at Wheatley near Doncaster in 1363 (or 1367).

III. From Past to Present

The Bailleul family lived in Normandy until the time of the Reformation. Those who were Huguenots were forced to flee because of their religion; they went to the Channel islands off the coast of France (but owned at the time by England). There is some speculation that the second "i" in the name was added to distinguish Huguenots from Catholics. These Baillieuls lived on the Isle of Guernsey for many years. Sometime during the early 1800s, a few members of the Baillieul family came to America. One of them was John Baillieul, who came to Nova Scotia, probably because of the Scottish influence in his family. John's son, Peter, had six sons, one of whom was lost at sea with his father. The remaining five came to the United States around the turn of the century, and settled in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Two of these sons, Alexander and James moved to Springfield, where they both found work with the Tabor Prang Art Co. They married sisters Edna and Estella Streeter, and raised their families. From New England, the family has branched out across the U.S.

REFERENCES:

(1) Pedigrees of Some of the Emperor Charlemagne's Descendants, Vol. III, by J. Orton Bock and Timothy Field Beard.

(2) Barnard Castle, County Durham, Department of the Environment: Ancient Monument and Historic Buildings, 1971.

(3) "Lineage of Barons Baliol"; from a genealogical history found in the Amarillo, Texas, Public Library.

(4) Her Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, by Peter Hammond, 1987, Department of the Environment, London, England

(5) Scotland from the Earliest Times to 1603, by William Croft Dickinson, 1962, Thomas Nelson and Sons, Ltd., London.

(6) History of the English People, by Green, vol .1

(7) History of England, by Hume, vol. 2

(8) A Student's History of England, by S.R. Gardiner

(9) Social England vol. 2

(10) A Short History of Scotland, by Thomson

(11) Encyclopedia Britannica, 1943 edition, vol. 2

(12) "The Balliol Family and the Great Cause of 1291-2", by Geoffrey Stell, in Essays on the Nobility of Medieval Scotland, K.J. Stringer, ed., 1985, John Donald Publishers, Ltd., Edinburgh.

(13) Balliol College: A History, by John Jones, 2nd Edition, 1997, Oxford University Press.

NOTES:

This paper is based on a summary history originally prepared by Linda Tanner as a school project, and later expanded by Thomas A. Baillieul using several additional source documents.

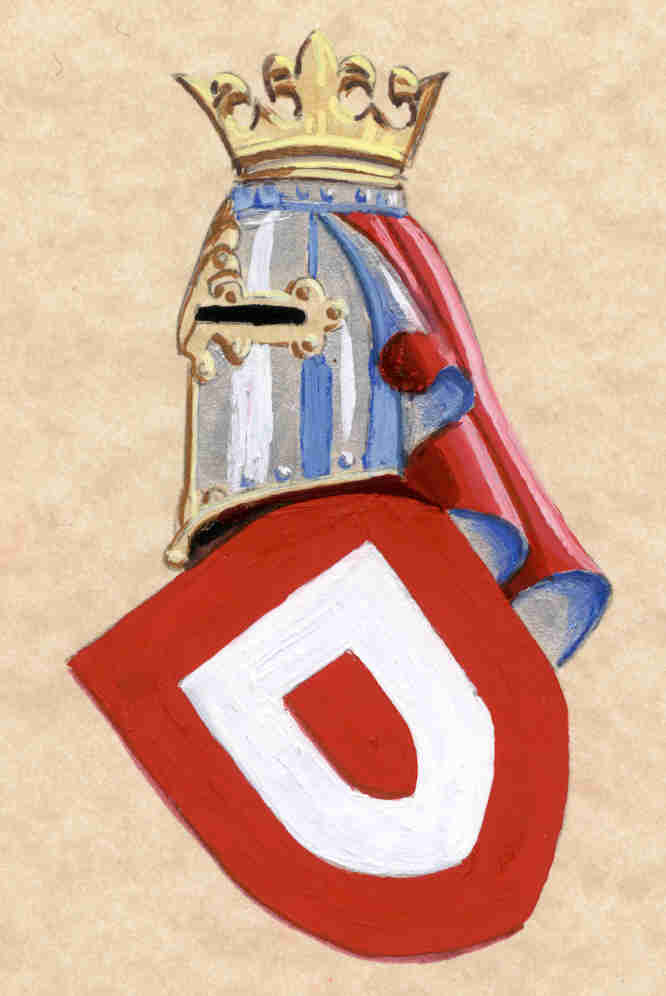

NOTE ON THE BALIOL FAMILY CRESTS

Eustace Baliol: d'Azur au faus escutcheon d'Or, crusule d'Or

Eustace Baliol: d'Azur au faus escutcheon d'Or, crusule d'Or

John Baliol: gules au orle argent

John Baliol: gules au orle argent Devorguilla of Galloway: d'Azure a lion rampant Argent crowned d'Or

Devorguilla of Galloway: d'Azure a lion rampant Argent crowned d'Or Combined arms of Baliol and Galloway, becoming the arms of Baliol College

Combined arms of Baliol and Galloway, becoming the arms of Baliol CollegeNOTES ON ONE MORE HISTORIC BAILLEUL:

During the 1070s the Byzantine Empire came under constant attack from the Seljuq Turks under the able leadership of Alp Arslan. The Byzantine army included a contingent of Norman mercenaries under one Roussel de Bailleul. When the Byzantine Emperor, Romanus, was put to death by a rival, Michael VII Ducas, Bailleul and his followers turned on their employers and marched on Constantinople. Michael VII Ducas, in despair, appealed to the Seljuqs for help. Sulaiman ibn Qutlumish volunteered his services, and with the help of an army of Ghuzz, the Normans were defeated.

Description

From the first, the castle was set in a commanding position on

the left bank of the Tees, on the borders of the Palatinate of

Durham, using the natural defense of an almost sheer cliff on

the west and south sides. The northern and eastern limits were

originally defined in the late llth or early 12th century by a ditch

and rampart to provide a roughly oblong-shaped fortified

enclosure, about six and a half acres in extent, covering an

important crossing of the river and center of communications.

The enclosure retained its boundaries throughout the Middle

Ages and it was not until the late 17th and 18th centuries that the houses of the townsfolk encroached upon and completely

masked the ditch on the east, eventually spreading into the wards themselves. There

were four wards of varying defensive strength with the nucleus, both defensive and domestic, in the northwest corner. The modern entrance is through the North Gate in the Town Ward.

Outer Ward

The original gateway to this ward was probably a little to the south of the King's Head Yard, but has been removed by later building behind the shops fronting the Market Place. A similar development has largely eliminated the east wall although its line is preserved by the main property boundaries, despite the encroachment into the ward of kitchen gardens. There is a slight mound inside the line of the wall which may be the remains of the up-cast bank from the ditch now filled in. The wide ditch on the north, which still exists for most of its length, is really the outer defense of the Town and Middle Wards. On the other three sides the walls are incomplete and in several places have been rebuilt. In the late 18th century they were described as "featureless" and probably never were of great strength. It has been suggested that this ward served as a refuge for the townsfolk and their cattle. In 1538 there was a great stable for forty horses or more and used by the auditors, receivers and various visiting officers. A certain amount of medieval pottery has been found following ploughing, but the only obvious indication of occupation within it is a garderobe shaft corbelled out of the southern stretch of wall. Leland, in the 16th century, stated that "the first area hath no very notable thing yn it, but a faire Capel when be 2 cantharides". Part of an early 12th-century column respond and base, built into the wall of a cattle shed, and a double aumbry built into a neighboring garden wall may be surviving fragments.

Town Ward

Occupying the northeastern comer, this ward was much more strongly fortified and may have served as the main bailey for the first castle. In the north curtain wall is a gateway giving on to the Flatts. The North Gate probably belongs to the 14th century but may occupy the position of an earlier entrance. It has a roundheaded arch of two chamfered orders with chamfered jambs and impost. Above the arch is a narrow, rectangular window similar to two other windows in the curtain, one on either side. The gate was flanked on the west by a small solid drum tower. Internally, there are remains of a substantial, two-storied gatehouse with rooms on either side of and over the gate passage. On the west, a doorway from the Ward opens into an almost square room with a fireplace either side of and over the gate passage. On the west, a doorway from the Ward opens into an almost square room with a fireplace against the curtain wall. At the south-west angle projects the base of a garderobe turret with the remains of two latrine pits. The porter's lodge was sited on the opposite side of the passage and opening from it. This, too, had a fireplace, and had been subdivided to give a living room and a bedchamber.

Further to the south-west, on the counter-scarp of the Inner Ward ditch is a rectangular tower contemporary with the curtain. The projecting northeastern angle has the remains of a buttress, while the north-western angle employs a vertical bonding course in the curtain wall. The tower was a two-storey structure with a timber roof supported on corbels. The only other remaining feature as a blocked, first-floor window facing south. In 1538 it was used as a malt kiln and the tower as well as the curtain wall further west contain nesting boxes for pigeons.

North-east of the gate, the curtain wall retains traces of buttresses externally and, internally, splayed rectangular loops mostly blocked, with round-headed rear arches. In the north-east corner two such loops are at a higher level than those east of the North Gate and the two in the isolated length of the curtain to the south; another tower is said to have existed at this corner, but there is no conclusive evidence for it in the structure now surviving. Further to the southeast is the large Brackenbury's Tower, projecting slightly beyond the line of the curtain and extending about 30 feet behind it. It was named after Richard III's Lieutenant of the Tower of London, Sir Robert Brackenbury, and is said to have been a prison. The ground floor has a rubble, barrel-vaulted roof with an ashlar string course just below the springing of the vault. A large room stretching the length of the tower has a mutilated chimney in the north-eastern corner, and a recess on the south side. A small chamber opens to the north, lit by a blocked loop on the west. This room has been disfigured and much of the wall-face cut away. On the upper floor is another large chamber with a fireplace in the north wall and a garderobe chamber in the north-west comer. Access was by means of a mural staircase in the south wall. South of Brackenbury's Tower is an isolated stretch of curtain wall with two blocked loops. The south side of the ward retains its high, though much patched, wall of uncoursed rubble.

Middle Ward

Despite its name, this is merely a small and irregular area bounded by the early ditch of the Inner Ward, the ditch on the south cutting the major portion of the castle off from the Outer Ward, a later ditch linking the first two on the east and the cliff on the west. In the 16th century this ward was known as the Many Gates. It had entrances from the Outer ad the Town Wards and served as a link between them and the Inner Ward.

Part of the gate tower guarding the approach from the Outer Ward remains. The surviving west wall shows that it was of at least three storeys. It was known as the Constable's Tower. Three internally splayed rectangular loops remain in this wall together with the toothing for return walls: that to the north shows a vertical straight joint. Further north is the jamb of a door at a high level. The tower projects beyond the line of the now non-existent south wall of the ward and is in the line of the ditch. The wall on the west side crosses the ditch of the Inner Ward and in doing so attains a considerable height. It has a round-headed opening at the ditch bottom similar to that which can be seen in the curtain east of the Round Tower, where the wall crosses the ditch. The original height of the opening is not yet known; it was no doubt a drain linking the two parts of the ditch. A gatehouse with a drawbridge existed in the east wall guarding the approach from Town Ward. The drawbridge pit and gateway have been uncovered, and a modern bridge spans the ditch between Town and Middle Wards. A survey of 1592 mentions the buildings in the ward at that time: a smithy, three stables, the great bam, the garner, two chambers over the gate, lodgings, a hall, Mr. George's Chamber and the Mill house.

Inner Ward

This ward contained all the most important buildings in the castle and largely for this reason its building history is very complex. Its full elucidation will not be possible until the area has been excavated archaeologically. The first castle appears to have been a ring work, a fortified earthwork edged by a wide, deep ditch and up-cast bank curving around to the steep cliff on the west and enclosing an area roughly oval in shape. It may have been defended by a timber palisade, for none of the existing masonry can be certainly dated to the late 10th or early 12th century. The substitution of stone walls for wood to form a shell-keep probably followed in the latter part of the century. Subsequently there were several rebuilds and remodels of the surrounding wall and the structures built against it. An area in the center of the ward has been examined and the resulting depression indicates the top of the earth rampart, the outer line of the ranges of buildings on the west, and the level of a late courtyard.

The ward was entered at the south from the Middle Ward, through a gatehouse set on the edge of the cliff. Only part of its west wall remains; this has one splayed loop with a flat lintel and evidence for a chimney flue in the upper storey. It is called the Headlamp Tower.

Opposite the gatehouse, in the northern corner, is the Round Tower, sometimes called the Baliol Tower, dominating the whole castle, half within and half without the curtain. It stands on remains of an earlier structure of uncertain date and plan, one wall of which survives in the east side of the well beneath the lowest floor of the tower. The tower is about 36 feet in diameter and about 40 feet high from the Courtyard. The lowest six feet are battered, but above that the walls are vertical, built without ornament in fine, coursed ashlar. A large spur provides the south and east sides with a rectangular external face. The apex of the spur dies into the tower about four-fifths of the way up. The tower was approached through the building which adjoined it on the south, with which it was connected both by the round-headed opening at first-floor level and by the passage which leads into the basement. A narrower mural passage on the left of this leads to a garderobe lit by a small loop. The large basement room, the floor of which was lower than it is at present, has a flattened dome vault built of rubble set in a spiral fashion. In addition to the well, there is a fireplace and the room is lit by three very long loops, slightly fish-tailed at the bottom and deeply splayed on the inside. One loop has been mutilated by the insertion of a later window. On the right a door with a flat lintel, later cut into a rough arch, leads by six steps into a small barrel-vaulted room within the spur, with the remains of a loop on the east. The opening in the north wall is modem. From this room a mural stair leads to the first-floor entrance from "the Great Chamber" on the south of the tower. This entrance leads into a room which has traces of a fireplace and a round-headed window with a view up the Tees. On the left a garderobe is reached through a passage in the thickness of the wall. The first-floor room had its own garderobe projecting to the north-east in the angle formed bv the curtain walls. From this room a mural star leads to the second floor, which according to a 16th-century inventory was called "My Lady's Chamber". In the north-east side a window has been remodelled with the insertion of a mullioned three-light window of the 16th century. This room also had a fireplace. An opening from the mural stair led to the roof of "the Great Chamber" while the stair continued to the third-floor room and the entrance to the wall-walk of the curtain on the east. A loop on the north-east has the rebate and one hinge for its shutter. The roof and parapet have gone. The Round Tower was built probably towards the middle of the 13th century.

South of the Round Tower and contemporary with it was a narrow two-storied range of rooms between it and the Hall. The return wall on the south contains the lower part of the jamb and sill of a window showing that it was free-standing-, perhaps an early hall. The ground floor was originally about 3 feet lower than at present, as can be seen by the hearth level of the large fireplace built into the spur of the Round Tower. The threshold of the small postern in the curtain to the west is lower still. The joist holes for the floor appear along the south side of the Round Tower but there is no trace of the return wall on the east. The upper floor was known as "the Great Chamber" in the 16th century and also contained the "drawing or privy chamber and the principal lodging chamber". In the curtain is an oriel corbeled out from the wall, blocking an earlier loop below. It is approached by modem steps. The window is mullioned with five lights and is probably a witness of Richard, Duke of Gloucester's occupation of the castle at the end of the 15th century, as the carving of a boar in relief within a border of interlace ornament appears on the soffit of one of the exceptionally large cover stones of the oriel. Three of the mullions are modem replacements. It is not clear how the range was subdivided.

The Hall in its present state belongs to the early 14th century, and may be the work of Bishop Bek. The curtain has been rebuilt in large squared rubble, distinct from the earlier work, with a chamfered plinth externally and two fine windows of two lights, each having ogee heads and transoms, and with an oval quatrefoil above. They are grooved for glazing and had stone seats. That there was some later rebuilding is shown by the large coursed rubble of the top eight courses on the inside. The hall was of ,,ground-floor" type and was known as the Great Hall in the 16th century to distinguish it from others in the castle.

To the south of it was the Mortham Tower of five storeys including a cellar. In the 16th century it was called "the West Tower which containeth the lodgings". It does not look as if it was ever primarily of military importance. It was probably added to the early curtain wall in the early 13th century from the evidence of an acutely arched doorway leading into a ground-floor garderobe. The tower was then heightened with a turret projecting from it at an angle in the 14th century. The turret, which probably contained garderobes, continued to the height of the tower, 'but much of it has collapsed along the cliff face in comparatively recent times. It contains a number of rectangular windows and doorways with hollow-chamfered moldings. Externally the later work is very distinct in its masonry style and its molded string course.

The eastern stretch of curtain bas been much patched and rebuilt. From the Round Tower to the small Postern Tower, the rubble masonry is largely a later rebuilding on the original line of the curtain. The postern takes the form of a dog-leg passage through a two-storey polygonal tower giving access to the exterior of the curtain and the scarp of the moat. The outer doorway with a bar molding near the springing of its arched head dates from the middle of the 13th century. The tower is built in coursed ashlar with a chamfered plinth that continues from the tower southwards along the curtain wall. Above the postern was a small chamber lit by two loops, one with a cross eyelet. Further south a straight joint in the thickness of the curtain wall indicates one side of a blocked mural passage and externally there is a blocked loop originally served by this passage. This length of wall also retains part of its parapet and wall-walk. A pilaster buttress of one build with the curtain possibly provides evidence for an initial construction date in the late 12th century.

Further to the south there is a larger tower projecting from the curtain to the lip of the moat, half-octagonal in plan. It is of coursed rubble with ashlar quoins, later in date than the curtain, and has its plinth at a higher level. lt was strengthened still later by two elaborate buttresses in the 15th century; the underpinning of these and of other parts of the tower is modern. Within the tower is a barrel-vaulted chamber on the ground floor and the remains of a similar vault in the chamber on the floor above. Both had been used in prisons. There is a large recess in the east wall and a fireplace in the north; the room is lit by a large loop. There is a garderobe on the south approached from the entrance to the upper chamber. The remains of toothing and two corbels at a high level indicate the position of an external stair to the wall-walk of which some of the parapet remains. The continuation of the curtain on the south no longer exists much above foundation level and the waging now visible is modern.