A History of Coast to Coast

A History of Coast to Coast

A History of Coast to Coast

A History of Coast to Coast

Following the success of his historic transcontinental solo flight in 1927, Charles Lindbergh turned his energies to another challenge - commercial aviation. He had a vision of

transcontinental passenger air service, linking New York and California. Recognizing that an

undertaking of this size would require substantial financial support, he turned to the backers of

his transatlantic venture with his new vision, and together they set off to make it a reality.

Having money of course was not enough and the investors began a search for business acumen;

their first target - Henry Ford. Ford declined to invest in the new venture, saying that his

business was "manufacturing, not operating." He did, however, allow the group to use his name,

and he also had a few sage pieces of advice. Up to that time, air travel was a novelty. Ford

cautioned that public acceptance of this new mode of transportation would depend on the

perception of safety. One passenger fatality in its early years would be all that was necessary to

kill the industry. Ford recommended that Lindbergh and his team use only the most modern of

equipment - monoplanes, because they were simpler; planes made of metal, because metal's the thing of

the future; and aircraft having more than one engine, for safety. Not surprisingly, the Ford Trimotor met all criteria!

The investors now sought an individual experienced in the business of aviation. They

turned to Clement M. Keyes, Canadian entrepreneur and then chief executive of the Curtiss Airplane Company. Keyes had

control of a holding company which owned a small operation known as Transcontinental Air

Transport (TAT). Keyes was definitely interested in the new venture and suggested that they all

approach a railway company to take advantage of rail's experience in timetables, ticketing,

baggage handling, station layout - all the things necessary to move people from place to place.

After several failed overtures to major railway companies, Keyes arranged a meeting with William W. Atterbury, head of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

Initially the new air service would combine air and rail transit until the route could be lit

for night air travel. Lindbergh spent nearly a year laying out the route to be followed. He

initially chose ten cities spaced out between the coasts. The plan was to have passengers board a

train at New York's Penn Station for an overnight trip across the Alleghenies, arriving in

Columbus, Ohio, the next morning. There the travelers would walk from the train station across

the street to a new air terminal where they would board a Ford Trimotor for the first air leg of the

journey. After a number of stops in the mid-continent, the plane would complete its day's journey

in Waynoka, Oklahoma. In Waynoka, the ritual was reversed. Passengers were shuttled to the

Santa Fe railroad terminal (Pennsylvania Railway's service did not extend beyond the

Mississippi) for a night's journey across the plains and desert to Clovis, New Mexico. From

Clovis, another Trimotor carried the passengers by day across the Grand Canyon and on into Los

Angeles. Coast to coast in under 48 hours!

All along the proposed route, towns competed for the honor of hosting a landing strip.

The Dodge City Daily in February, 1929, conceded defeat and congratulated Waynoka,

Oklahoma, as the chosen transfer point for the Santa Fe railroad.

Lindbergh was demanding in his specifications for the new air fields. His requirements

set the standard for air travel in the United States, and later the world. In Columbus, Ohio two

attempts were required to pass a bond issue of $850,000 for purchase of 700 acres and a new

terminal building (still in existence adjacent to port Columbus Airport along E. Fifth Avenue. The Pennsylvania Railroad then built a new rail station at the closest point on

their tracks to the new terminal, creating a covered walkway over Fifth Avenue for the

passengers' convenience. Already anticipating the time when night flights would become a

reality, Lindbergh ordered that the airports at Waynoka, Oklahoma and Clovis, New Mexico be

equipped with runway lights; and that new airports be built at Winslow and Kingman, Arizona,

also with lights.

Other improvements set in place by the farseeing Lindbergh included: a national

meteorological system which allowed updated weather information to be passed along to pilots

for each leg of the journey; radio communication between pilots and the ground (provided by

RCA); and teletype service between each of the stations (provided by AT&T).

Lindbergh himself was present for the inaugural flight. On the evening of July 7, 1929, a

train pulled out of Penn Station, arriving in Columbus, Ohio the next morning. There, thousands

of well wishers came out to watch the first plane take off - and to catch a glimpse of the "Lone

Eagle" ad special first passenger, Amelia Earhart.

Eventually, TAT acquired Maddux Airlines (1929) and merged with Western Air Express (1930), changing its name to Transcontinental and Western Air. With the advent of international service in 1950, the airline again changed its name to Trans World Airlines -- TWA.

Coast to Coast air/rail service lasted barely 18 months before being supplanted by round-the-clock air flights. Within four years new aircraft (the Boeing 247, and the Douglas DC-2 and

-3) became available which far surpassed the Trimotor in speed, load carrying capacity, and

comfort.

But even as equipment improved the basic concepts put in place by Lindbergh and his partners remained as the standard for air travel that we still enjoy today.

Return to EarthFriend Arts Home Page

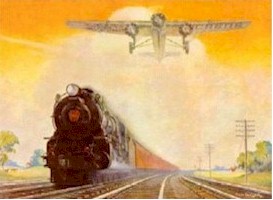

Note: The picture at the top of this page is "Giant Conquerors of Space and Time" by Grif Teller. The original oil painting was commissioned by the Pennsylvania Railroad for its 1931 calendar. The painting is in the collection of the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania.